Generative Adversarial Networks

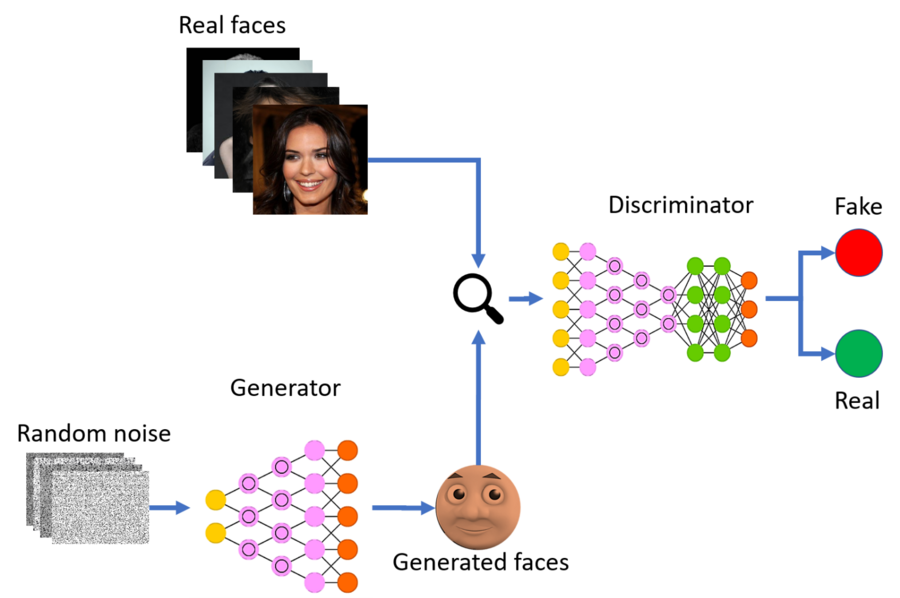

A generative adversarial network, or GAN for short, is a type of model with a special approach to generative modeling. Using two linked models, a generator and a discriminator, GANs can generate new data that resembles a given dataset, whether with images, text, or even music data.

A diagram of a GAN

A diagram of a GAN

The generator uses random noise to generate a sample of data. Because of this, its generated faces are not all the same. Then, in a sort of test, the discriminator tries to guess whether a given sample of data is real or fake. This sample of data is chosen randomly from the real and generated sets. When the generated sample is classified as real, the generator is “rewarded,” otherwise it is “punished.” More about the exact process by which this happens is covered here. Finally, after the generator trains for a few epochs, the discriminator trains, coevolving with the generator. They take turns and alternate so that each of the models can become better at “beating” the other. If they trained at the same time, it would be more difficult since it’s harder to hit a moving target. Once both of these models become really good at their jobs, the assumption is that the generator will produce realistic samples of data.

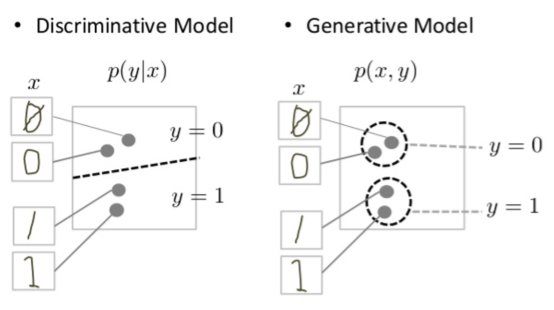

Note that the generator’s job is harder than the discriminators. As shown in the image, both of the models are essentially discriminators. However, the generator must be more certain about the boundaries it is drawing in order to then also generate more realistic data within those boundaries. In other words, generators model data distributions, while discriminators simply draw boundaries through them.

More concretely, generators must learn that “things that look like trees are more likely to be on things that look like land” and that “eyes and ears are unlikely to appear on the forehead.” These are obviously pretty complicated. By contrast, the discriminator only needs to look for a few important patterns to immediately know the image is fake.

The generator output and discriminator input are directly linked. Hence, through back-propagation, the discriminator can tell the generator exactly why it classified or did not classify its generated samples as real, so the generator can then use that knowledge to improve.

What types of GANs are there?

There are many different types of GANs, each specialized to its own generation task. Here are some of the types:

- Vanilla GANs: standard GANs that consist of a generator and discriminator

- Conditional GANs (CGANs): GANs take as input additional information, such as class labels. Both the discriminator and generator, which still receive random input, receive the additional class label, so the model learns how to generate data with more variety

- Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs): GANs that use convolutional neural networks in the generator and discriminator, commonly used for image generation

-

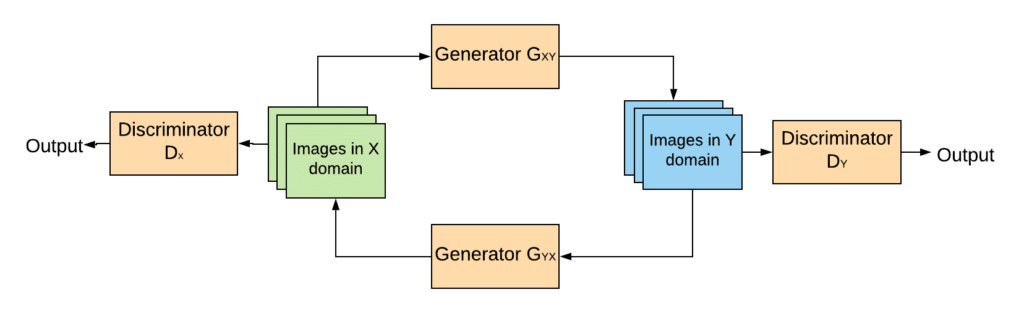

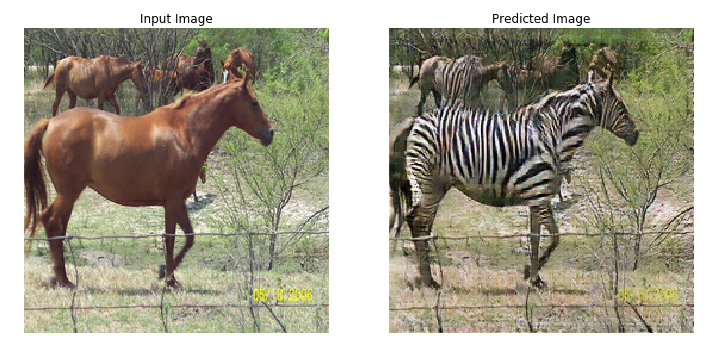

CycleGANs: GANs designed for image-to-image translation tasks. They do this by training two generators and two discriminators with a “cycle consistency loss” function, which assumes that if you translate an image of a horse into a zebra and back into a horse, you receive the same original image. They achieve great results in the absence of images, which are often difficult to obtain

The architecture of a CycleGAN

The architecture of a CycleGAN - Wasserstein GANs (WGANs): A variant of GANs that uses a different loss function to improve performance. More about them can be found here

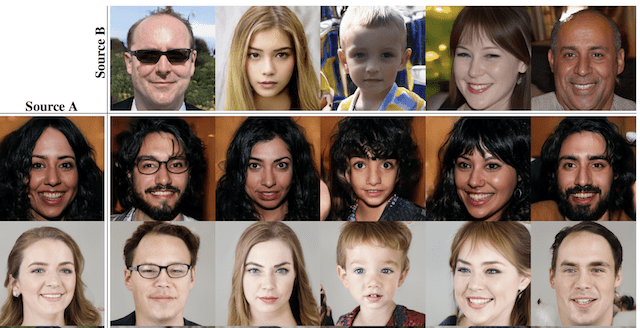

- Progressive Growing GAN (PGGANs): GANs that create higher-quality image data by incrementally adding layers to the generator and discriminator during the training process. Thus, first the model learns structure, then progressively finer details. This is unlike a simpler GAN, which might reach an undesirable compromise by attempting to do both simultaneously

The power of CycleGANs

How do GANs produce realistic image data?

There are many types of GANs, but here we will focus on DCGANs and generators specifically, since discriminators are simply CNNs. Essentially, the idea is that the random noise fed into the GAN is upscaled into image data. This is done by transposed convolutions along with different types of interpolation to fill in the gaps.

Shown here is a transposed convolution. In the same manner that convolution layers in CNNs apply filters to downscale an image, transposed convolutions apply filters and sum them to upscale an image.

By contrast, a deconvolution is the exact inverse of a convolution. These terms are often confused with each other. Still, the bottom line is that GANs upscale noise into image data through the application of filters, just like CNNs. These learnable filters are then altered through the training process to produce image data, through the same magical process that CNNs learn to identify road conditions and interpret street signs.

What are the shortfalls of GANs?

Maybe right now you are thinking GANs sound great, just as I did when I first learned about them. Still, they have many problems:

- Vanishing Gradients: The vanishing gradient problem is a menace to many different types of models that use back-propagation, and GANs are no exception. This problem derives from the loss function, where the generator tries to get the discriminator to output numbers close to 1 (a classification of the sample as “real”) with its generated sample while the discriminator tries to output numbers close to 0 (a classification of the sample as “fake”). Unfortunately, when the discriminator gets too good, it may begin to output numbers on the order of $10^{-10}$. Generators use this output to improve through back-propagation, but since it is so small, there is not enough information for the generator to make progress. Consequently, the generator stagnates and fails to improve.

- Many attempts to remedy this problem utilize modified loss functions. One notable example is the Wasserstein loss function, used in Wasserstein GANs (WGANs). In this system, the discriminator does not actually classify samples but instead tries to make its output significantly larger for real data than for fake data (because it doesn’t classify samples, it is actually called a “critic”). Similarly, the generator, G(z), tries to generate samples that would maximize the critic’s output, D(x). In other words, the discriminator attempts to maximize \(D(x)-D(G(z))\) while the generator attempts to maximize \(D(G(z))\) This system has been shown to be effective at remedying this problem, and as such it is the default for the TensorFlow GANs (TF-GANs).

-

Mode Collapse: Usually, the goal with GANs is to produce a large variety of realistic data. However, the generator is not incentivized to do this; its goal is simply to fool the discriminator. Thus, when it finds an especially effective output, it often learns to produce only that output. Ideally, the discriminator will adapt and learn the generator’s patterns, but this is not always the case; if it gets stuck at a local minimum, it may never learn its way out of the trap. As a result, the generator over-optimizes for the discriminator, becoming really good at fooling it with otherwise unrealistic data. The result is that the generator rotates through a small set of output types, and this is called mode collapse.

- Unstable Convergence: GANs, with their unique “competitive” loss, are known to be extremely unstable. Take, for example, a situation where a generator is producing extremely realistic data, often fooling the discriminator. In this state, the discriminator’s best bet is to essentially flip a coin to make its prediction, since it can’t tell the difference between real and generated samples of data. Unfortunately, this can be fatal for the generator, since it begins to train on this junk feedback and as it tries to adapt, its own quality may collapse. Imagine that you were a good student, but on the tests for which you studied very hard, the teacher whom you greatly looked up to began to give you randomly chosen grades that didn’t reflect your real performance. You would break down too! In this same way, a GAN’s convergence is called unstable.

Despite these problems, GANs have produced great results in recent years. Let us take a moment to appreciate what they can generate!

StyleGAN, a type of PGGAN

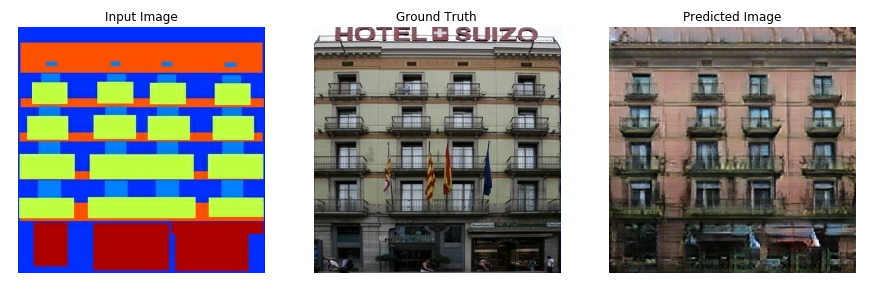

Pix2Pix, a type of CGAN

Stable Diffusion, given the input “photograph of an astronaut riding a horse”