Making the Mask Classifier

Here’s a bunch of questions and answers on how I made the mask classifier at this link. Feel free to use the sidebar on the left to go to a specific header!

How was it made?

The mask classifier was made using TensorFlow. TensorFlow is an open-source software library for machine learning and artificial intelligence, commonly used in Python.

Using TensorFlow, anyone can pretty easily create and train models. If you are interested, here’s the Kaggle link to one of my older versions.

Here are some interesting details about the model: It was trained for only 14 epochs, or passings of the entire training data, which is not a lot in the context of some other models. In the dataset I ended up using, there are about 12,000 images. Each of these epochs took about 140 seconds, meaning it trained for just over 30 minutes. In this time, it reached a 97.62% validation accuracy. It was trained using the ReduceLROnPlateau and EarlyStopping callbacks and a technique called transfer learning. The model I used for feature extraction was MobileNet V2. If you don’t understand these terms, I clarify what they mean here.

After training the model, I converted it to a model that could be used on a web browser using TensorFlow.js. However, this is about 1000 times easier said than done. After many hours of installing, reinstalling, and checking Stack Overflow, I downloaded tensorflowjs through Google Colab, and the conversion there ended up working for me. Finally, I modified a script from this video so the site could detect and classify faces in real time.

What is the model doing?

Depending on your knowledge of machine learning, you may or may not know that the so-called model or neural network that is behind the scenes figuring out whether you are wearing a mask is essentially just a bunch of numbers. So how does the model “see”?

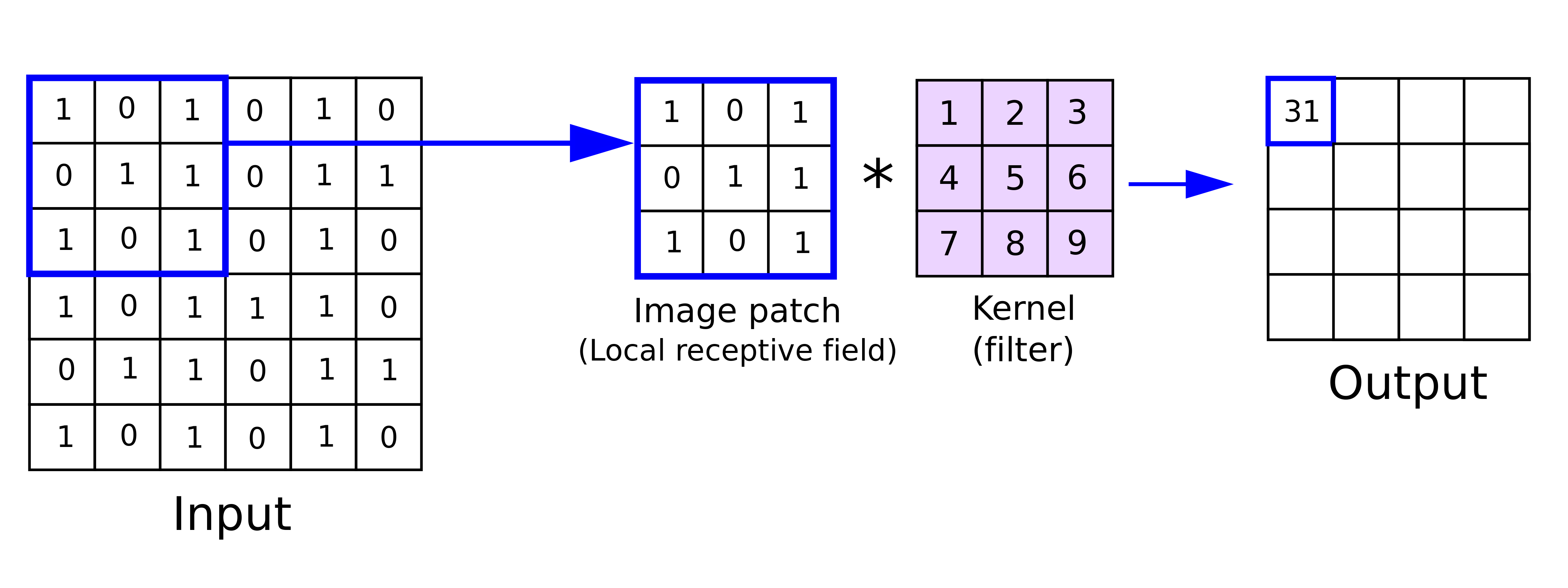

The answer is a deep learning algorithm called a convolutional neural network, or CNN for short. CNNs are specifically designed to process pixel and image data, which is why they excel at image recognition tasks such as this one. They do this using an operation called a convolution, which is applied to the image in a convolution layer. When a convolution is applied to an image, the model slides many learnable filters, or kernels, across the image. These kernels are much smaller than the image; for example, the image might be 128 pixels by 128 pixels, while the kernel is only 3 pixels by 3 pixels. Each of the pixels in the kernel has an activation value that is multiplied by the subset of the image that the kernel is over. These multiples are then summed and used to create a new, smaller image.

The 3x3 kernel is applied to the 6x6 image; In this case, the output is 1+3+5+6+7+9=31

The 3x3 kernel is applied to the 6x6 image; In this case, the output is 1+3+5+6+7+9=31

More about CNNs is covered here. The genius of convolutions is that they mimic human vision, specifically feature detectors, and how incredibly responsive we are to patterns in information.

These layers, which are applied many times, simplify the image to respond to learnable patterns. While we cannot consult the model to see what patterns it is looking for (again, it’s just a bunch of numbers), you can imagine how a specific part of the output may measure the presence of a nose or mouth. It’s easy to see how this information could be used to infer whether someone is wearing a mask.

But how might a computer learn to infer? This is covered in the back-propagation module, but to simplify, the model is “rewarded” and “punished” for every image-label pair. Through this process, it “learns” by updating its own parameters to be rewarded more and punished less, although this process is more mathematical than like training a dog.

On the website, there are actually two neural networks working their magic. There is my model, and there is BlazeFace, a speedy fast and lightweight face detector model. The output of this model, which has the coordinates of the supposed face, is then sliced and transformed into a 224-pixel-by-224-pixel slice, which is then input into my model. Ultimately, the model simply outputs two numbers: the probability that the face is wearing a mask and the probability that it is not. Then, based on this “prediction,” the color of the box and text are updated accordingly. That’s all! All that work to classify whether you are wearing a mask or not, which you can do with a simple glance and in milliseconds.

Why is the model so easy to fool?

Yes, I know! When you look off to the side, the model thinks you are wearing a mask. Similarly, when you cover your face with a non-mask object, the model thinks you are wearing a mask. These are cool and all, but I think it’s more interesting to examine why exactly this is happening.

First, as a disclaimer, we can’t be sure why this is happening. The model is just a bunch of numbers, and we can’t ask it questions or examine what it’s thinking. However, here are some of my theories:

The Data

Inevitably, that data is where the model learns all of its knowledge from. Thus, undesirable trends in the data become quirks in the model. For example, naturally, there is more variation among the pictures of faces wearing masks. As stated in the dataset description, the images with masks are scraped from Google, while the images without masks are taken from the CelebFace dataset by Jessica Li.

The most “angled” faces of the first 30 images in the both datasets

Obviously, the pictures of celebrities are more standardized: they are facing the camera. This is not the case with the mask-wearing images, which are pulled from numerous sources and comprise a large variety of face angles and resolutions. In other words, rather than detecting whether you are wearing a mask, the model might have learned to predict if you are looking to the side, since most of the images of faces looking to the side were in the mask-wearing pile.

An image in the mask-worn dataset

The issue of data also explains why non-mask objects are perceived to be masks. The model does not know what a mask is; that was not its task. Instead, its task was to classify if people were wearing masks, and from the data it saw, it learned that the mouth and nose are usually covered when a mask is worn. Thus, when whatever specific pattern the model is looking for is satisfied, perhaps that the nose and mouth are covered, it assumes you are wearing a mask. This applies whether the object covering your face is a mask or not.

The Webcam

Remember that the model is neither trained on images from a webcam nor made for live mask detection. Instead, the model was trained on images of faces wearing masks, and its application in a live mask detection app is a testament to its generalizability since it seems to work on new data.

This also explains some of the quirks we see. For example, if you put your face at an angle, as we’ve discussed earlier, the model thinks you are wearing a mask. But then, when you pull your face away, at some point, the model changes its prediction without you ever changing your face angle. This, among other quirks, is likely explained by webcam resolution. As you pull your face away, the model is fed worse and worse quality face data. Apparently, this must make it harder to discern whether you are wearing a mask, since the model defaults and assumes you are not.

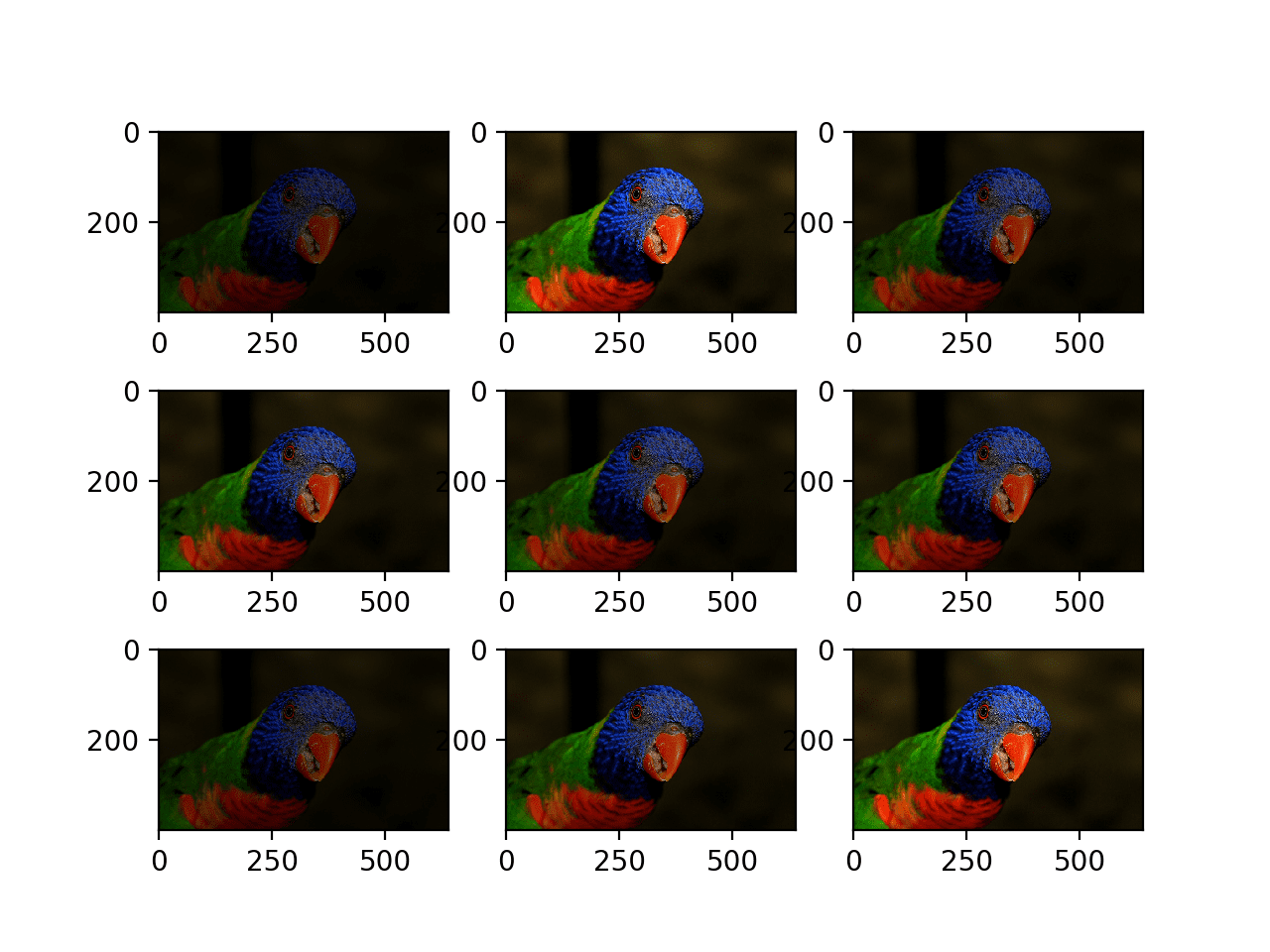

An example of data augmentation with brightness levels

An example of data augmentation with brightness levels

Lastly, the model on the website is actually the second version. The first model I trained reached a validation accuracy of 93.76% but performed a lot worse in live mask detection. I noticed that the model only worked well in specific lighting conditions, so using data augmentation, I trained the model to be better at different lighting conditions, and it ended up working well!

What do the words mean?

| Word | Definition |

|---|---|

| Epoch | An entire passing of the training data through the model |

| Hyperparameter | A machine-learning parameter, or value, that affects the model and is chosen before the learning algorithm is executed |

| Learning Rate | A hyperparameter that controls the pace at which the model minimizes the loss function |

| Validation Accuracy | Accuracy of the model on data it was not trained on |

| Training Accuracy | Accuracy of the model on the data it was trained on. The model tries to maximize this metric |

| Overfitting | This occurs when the model cannot generalize and instead essentially memorizes the training data. This is especially possible with large models because of the greater number of neurons. A telltale sign of overfitting is when the training accuracy is high but the validation accuracy is low |

| Callback | A type of function that is applied to a model during training, usually to improve performance |

| ReduceLROnPlateau | A callback that reduces the learning rate when a given metric, such as accuracy, has plateaued. Models often benefit from this |

| EarlyStopping | A callback that stops the training when the validation accuracy of the model begins to decrease or slow down in order to avoid overfitting |

| Transfer Learning | A research problem that involves applying what one model learns for use in another task. In this case, I used transfer learning to train fewer layers attached to a larger frozen model that was originally trained on a much larger image dataset. Often, this reduces training time and increases the final validation accuracy |

| MobileNet V2 | A family of neural networks that are specialized for image classification and running on smaller devices. This is the larger model on which I used transfer learning to adapt to the mask classification problem |

| Feature Extraction | In general, feature extraction refers to reducing the number of dimensions used to describe a dataset, essentially finding important features of the data. In this case, feature extraction refers to how MobileNet V2, after being trained on a much larger dataset, likely detects meaningful features of the image, such as the presence of a nose or mouth |

| Convolutional Neural Network | A class of neural networks commonly used for image classification and related tasks. It excels at these tasks through operations called convolutions |

| Convolution | An operation that extracts various patterns from an image through the application of filters. Mimics the feature detectors of human vision |

| Data Augmentation | The process of artifically increasing the amount of training data by slightly altering existing data, especially to improve model generalization |