Connect 4 MCTS

MCTS (Red) finds a nice win against a real player

This project is an implementation of Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) for Connect 4. Find the code for this project here. Briefly, MCTS is a simulation-based algorithm that uses random sampling and heuristics to make decisions in a game or problem-solving scenario. Generally, there are four steps:

- Selection: traversing the game tree to select a promising node while balancing exploration and exploitation. This implementation uses UCT (UCB applied to trees)

- Expansion: add the child nodes of the promising node

- Simulation: complete random play-outs or rollouts for each child

- Backpropagation: update the statistics of the nodes along the path from the root to the selected node

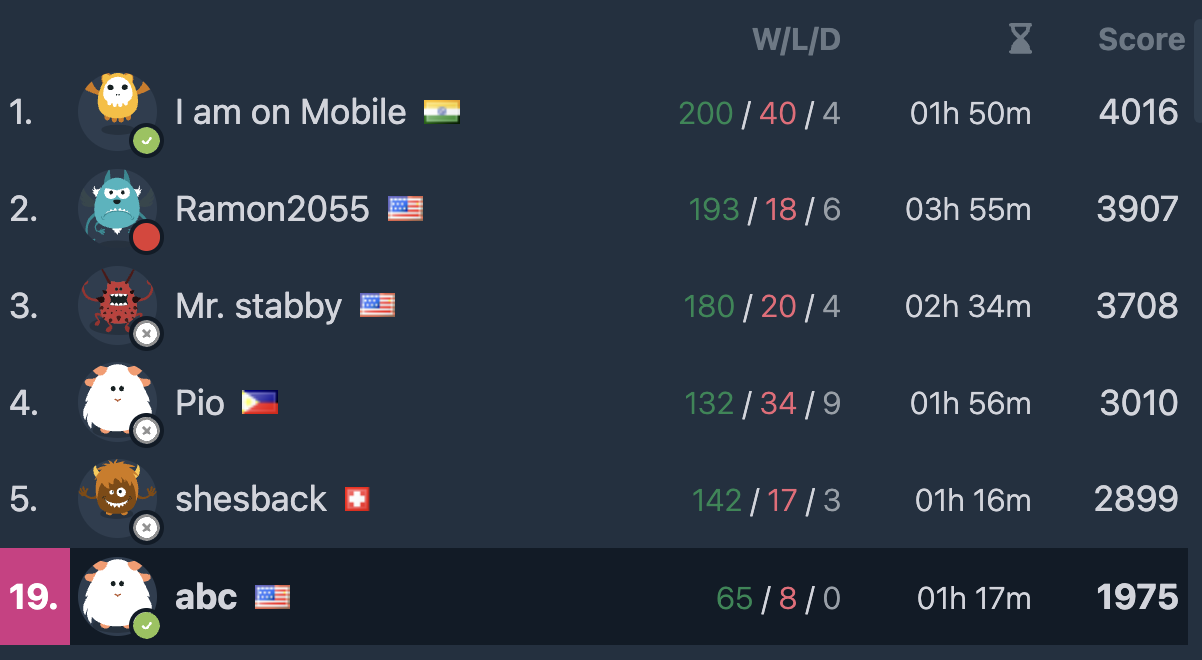

Results

In a public tournament, the bot was able to place in the top 1% (19/2460), with an impressive record of 65 wins to 8 losses. Note that it’s likely other players used similar tools. Wins ranged from those against guests to accounts with almost 50,000 wins.

On my machine, I was able to complete 29,403,700 rollouts in 70.8770 seconds.

- That’s 414,855 rollouts per second over 1,470,185 nodes total!

- This performance was achieved through Numba

Connect 4 is a solved game. Assuming optimal play, the outcome of the game is fixed based on the first player’s move:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2 wins | P2 wins | Draw | P1 wins | Draw | P2 wins | P2 wins |

With this knowledge, I benchmarked the model before and after tuning by playing it against itself, fixing the first move. Note that c is the exploration parameter of the UCT algorithm, and the model completed a cycle of MCTS with every move.

Before: c=1, 1000 nodes, 10 rollouts/node | | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |—|—|—|—|—| | P1 wins | 30 | 63 | 71 | 79 | | P2 wins | 65 | 35 | 26 | 20 | | Ties | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

After: c=2, 1000 nodes, 20 rollouts/node

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 wins | 28 | 44 | 51 | 57 |

| P2 wins | 69 | 55 | 41 | 43 |

| Ties | 3 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

After tuning, the results seem to match up better with the expectations (with a win for P2 and a draw in columns 1 and 2, respectively). The board is symmetrical, so no tests were performed for columns 4-6. Compare these results with the model’s original predictions on P1’s chances of winning after 29,403,700 rollouts:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 wins | 0.463 | 0.507 | 0.518 | 0.527 |

It’s pretty optimistic! Another fun fact: 393,444,840 rollouts were completed to simulate 100 games in the 0th column.

Notes

Dealing with terminal states (i.e., states that end the game) was extremely troublesome. My main difficulty was coming to the realization that

terminal states inform the states that lead to them through backpropagation.

To speed up computation, my earlier implementations overlooked states that were won. After all, why simulate a game when its outcome is certain? Then, I started to notice strange behavior, such as the AI making moves that seemingly handed its opponent an immediate win. This is because,

at its heart, MCTS has no knowledge of the game. It simply makes random moves.

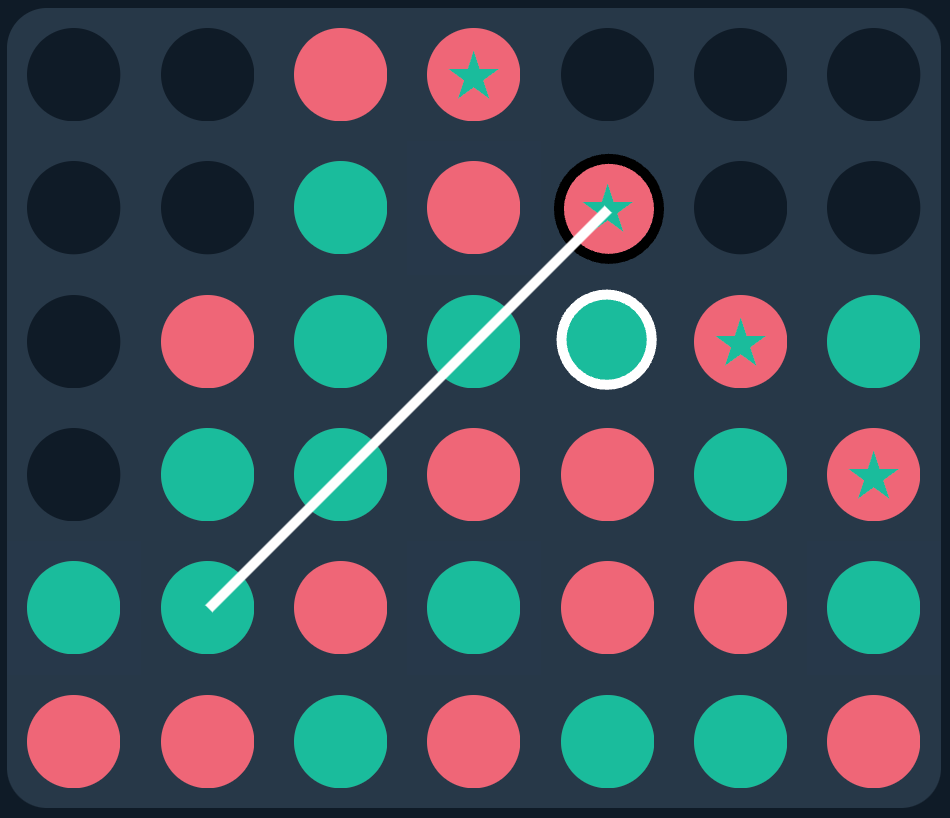

Consider the following game state, which I encountered while facing the AI off against real players:

The AI made the move in white, which was immediately followed by the winning move in black. How could it make such an obvious blunder?? Then it hit me: since the AI doesn’t simulate terminal states, it didn’t even consider the move in black. Instead, it considered every other move by red—each of which would’ve allowed the AI an immediate win, playing in the exact slot that was overlooked—explaining why it made the move in the first place.

The updated implementation takes the opposite approach, not only simulating terminal moves but also prioritizing them, allowing them to inform all the nodes above them.